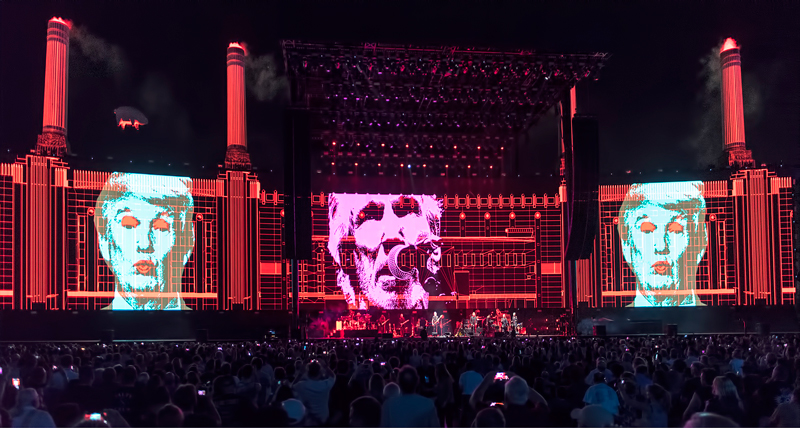

In 1977, when the Battersea Power Station adorned the cover of Pink Floyd’s 10th studio album, Animals, it represented the rise, apex, and fall of a post industrial England. Commissioned in the late 20’s, and built to herald and accommodate the rising demands of the new consumer-class culture that was birthed after the great war (WWI), the Battersea exterior featured a late ‘moderne’ Deco design that was only suggestive of its full and opulent Art Deco interior. Planned as two stations, Station A was phased online between 1933-35, but Station B wouldn’t see completion until well into the 50’s. Considered the largest brick building in Europe, it was a beautifully imposing structure with an industrial majesty that was reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.[1]Readers will note that The Musicopolis also borrows from these design aesthetics Crushing coal into powder to fuel its giant furnaces and boilers, the Battersea survived the Great Depression, the German Blitz, the Nationalization of the British power industry, and the collapse and bankruptcy of the British Empire that followed immediately from the end of WWII; presiding over the creation of the welfare state, and through the years of austerity and rationing and a general political unrest under largely conservative governments that plagued the UK until the 90’s. In disrepair, and in its final years of operation before its turbines were shut off forever in 1983, the Battersea was already a dead horse when Pink Floyd captured that image for posterity, but the power of the image, and the symbol of the social brutality it seemed to embody, accrued a mythic power of its own. This, and the absurdity of the superimposed “flying pig” over the station, gave the Animals cover all the Orwellian resonance it needed to become a pop culture symbol of the machinations of the oppressor over the oppressed, and made it a dorm-room poster staple all over the world.

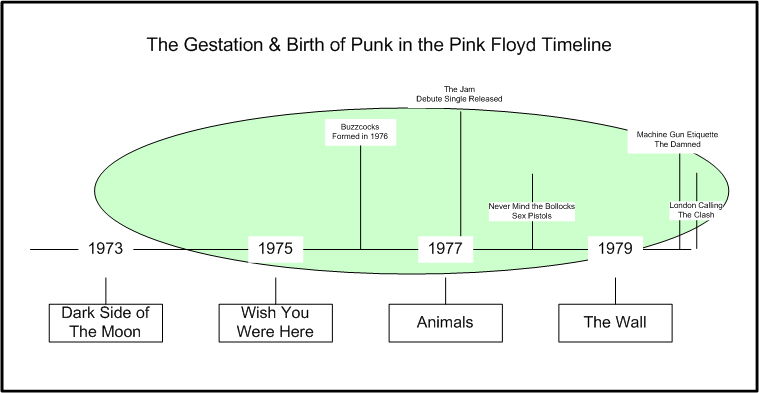

With the success of 1973’s Dark Side of the Moon, and its follow-up, Wish You Were Here, it would be safe to say that Pink Floyd was on top of the world both commercially and creatively through the early to mid 70’s. You could argue, in the post Sgt. Pepper universe, and with the birth and ascendance of the album format in the North American market, that Pink Floyd’s successes saw them grow alienated from their UK audience. For that post-war generation that came of age during the early years of British austerity, the trappings and the excesses of the rock star lifestyle were a lived-out fantasy inspired by the collective memory of Rule Britannia and the glory days of the Empire. Rock stars of that generation lived their success like indulgences, and the generation that followed them, sometimes their own younger brothers and sisters who had themselves only known of a life of social, economic, and political strife, began to reject them. Big British bands like Floyd, The Stones, and Zeppelin, along with many of their prog and glam styled contemporaries, found themselves increasingly out of favour with the youth of their home country. You might say that the British Invasion preceded the feeling of British Abandonment, and as the 70’s wore on, a new underground political and musical ethos began to take form. From out of that ethos was born a unique (and very UK) brand of Punk Rock.

Although you weren’t reading about members of Pink Floyd living in listed French estates, or hearing of their wild or lavish indulgences with sex and drugs, they still suffered the taint of disfavour. Their excesses were typified by the increasing costs of their album productions, and their near permanent residency inside the recording studio in their pursuit of sonic perfection and craft. The drive towards sonically superior albums as studio created masterworks, and elaborate tours and performances that were more and more theatrical, created a new generational divide. As the music became more rich and complex, and the levels of production so highly articulated and fetishized (and almost economically unattainable for up and coming young musicians to follow), bands like Floyd found themselves on the outside for the first time since their ascendance into rock royalty.

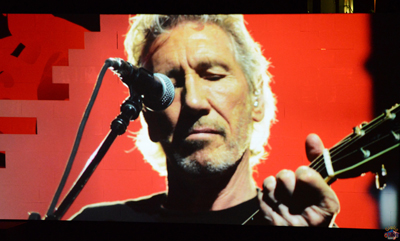

Roger Waters by Giulio

Roger Waters himself, Pink Floyd’s bassist, singer, and principle songwriter/conceptual leader, wasn’t blind to this estrangement. Originally founded as a psychedelic band fronted by the gloriously unstable genius guitarist/singer/songwriter Syd Barrett, Floyd had slowly matured into a cohesive progressive (prog) rock band led by Waters, with creative tensions triangulated between Waters, guitarist David Gilmour (who replaced Barrett in 1968) and keyboardist Richard Wright. After Syd’s departure Rogers had developed into the band’s main creative visionary, and Floyd’s 70’s masterworks were essentially his conceptual creations. Roger’s work always had an element of the political in them, but they were also deeply personal at heart. He told and staged big stories, sometimes working through grand and flighty concepts, but in the center of it all was always an individual – it was him. And within all those narratives there was still the machine; the machine of war, the machine of time, the machine of industry, and the machine of capitalism. For Animals, Waters felt the need to retool and strip away some of the wet breathy accoutrements of the Pink Floyd sound and legend, and distill them into a more streamlined and dry narrative. He didn’t want to take you into space anymore, or wish you to himself somewhere- he wanted something more stark, more stripped down – something more unforgiving with a motor. With Animals he gave us exactly that.

Pigs (Three Different Ones) by Al Case

Telling an Orwellian influenced tale that divided people into social hierarchies fueled by the machinations of capitalism (a near inversion of the Orwellian anti-socialist treatise that was Animal Farm), Animals presents to us as a morality play about Dogs, Pigs, and Sheep. Was this Waters’ response to the growing punk anti-establishment ethos? Unlike the punk movement, which gravitated towards collective identities (be they fascist, socialist, or anarchist) that were infected with nihilistic resignation, Pink Floyd’s Animals offers a critique of all three classes in appropriately named songs which are curiously book-ended by two very beautiful and personal compositions that remind you that the individual still exists within these structural hierarchies that keep turning and trading off with machine-like precision. Listening, the stripped down and stretched out linear nature of the narrative within Animals is suggestive of a program of self-imposed sonic austerity for Floyd – an attempt to get their boots on the ground. But the metaphors of flight, and Gilmour’s fiery guitar leads (punctuated by a pace setting staccato rhythm) still lift the music into a ethereal plane that is neither physical nor wholly metaphysical. It is instead a liminal space where the narrative moves forward like a train on the rails destined for some unknown destination. And in the midst of it all, the idea that two people might just find comfort and joy in love, and transcend it, is the redemptive blanket in which the whole album is wrapped. In that sense, Animals doesn’t simply reduce human life into an animal themed allegory about the brutalities of capitalism – it proffers love as a uniquely human quality of being in which we can all find reprieve to fly away and escape it. But there’s a warning: keep an eye out for Pigs on the Wing.

Photo Credits:

Feature Photo Credit: Battersea Power Station, by Dario-Jacopo Lagana via flickr, (CC BY-ND-NC 2.0)

Roger Waters by Giulio via Flickr, (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Pigs (Three Different Ones), by Al Case via Flickr, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Notes & References

| ↑1 | Readers will note that The Musicopolis also borrows from these design aesthetics |

|---|

4 comments

Outstanding deconstruction of this classic album. Many great points not raised by other reviews. I especially liked how you connect the building’s rich and overlooked history to its symbolism of the album. Also some great observations on the growing tension between punk vs the rock establishment of late 70’s Britain. And your conclusion on Gilmour’s guitarwork as “liminal” might be one of the best description of his sound I’ve ever read.

Thanks SM – I really appreciate the feedback. I’m trying to make sure the stuff we publish here resonates with people on a bit deeper level but has some rigor and a little philosophical depth too, so your comments really made me feel we got a good balance on this one. We hope to slowly grow our readership as we add more articles and more authors to the site. We’re taking it slow and easy right now but hope for a little more momentum in the new year. We’ve got articles on Living Colour, The Black Rock Coalition, & another article coming profiling a fantastic musician who recorded a full album cover of Animals… hopefully some cool things. Thanks again – many kind regards. Rob.

So that article profiling the musician who did the full cover of “Animals” – when’s that coming out? I’ve been dying to read it.

Great question! The article is still underway – We had hoped to release it at the end of Spring but it’s most likely still about 4 weeks out. Keep your eyes posted.